Mark Kermode goes on to challenge producers into making blockbusters smarter, since being smart or not is not one of the factors that determine a film's success. I'm afraid though, that "dumb" blockbasters are just another part of the distracting media and trash pop culture which overwelms the Western world. /od

------------------------------------------------------------------------

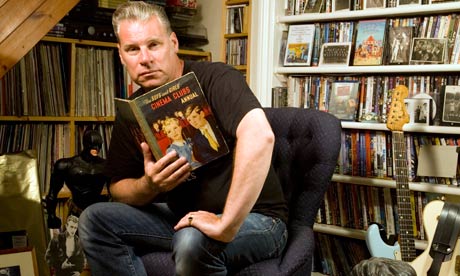

In this highly charged polemic, the Observer film writer and 5 Live critic tackles the big-budget producers for their cynical rejection of intelligent movies – and contempt for the ordinary cinemagoers who fill their pockets

Here are three absolute truths:

1. The world is round.

2. We are all going to die.

3. No one enjoyed Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End.

Let me give you an example.

When I was a student in Manchester I lived in a place called Hulme, a sprawling concrete estate of industrially produced deck-access housing that had been declared unfit for families in the mid-70s and had subsequently descended into oddly bohemian squalor. By the time I arrived in Hulme in the early 80s it was full of students who loved it, because the rent was incredibly cheap and nobody paid it anyway – the council couldn't evict you for non-payment because that would just make you homeless and Hulme was the place to which they sent homeless people after they'd been thrown out of everywhere else.

The architecture of Hulme was a strange mix of 60s sci-fi futurism and bleak eastern European uniformity, the kind of place JG Ballard had nightmares about. It was grimly cinematic, so much so that the photographer Kevin Cummins had used it as the background for his iconic photographs of Joy Division, the most existentially miserable band of the 70s. At nights, as the sun went down and the lights came up around the McEwan's beer factory, which wafted noxious fumes across the entire misbegotten district, it seemed more like a scene from Blade Runner than the landscape of a thriving northern town. At regular intervals gangs of straggle-haired youths, who appeared to have escaped from the set of Mad Max 2, would drift across the overpass that traversed the Mancunian Way, shopping trolleys of worthless loot pushed religiously before them and umpteen dogs on various bits of string prowling behind them picking off survivors. Occasionally, an incongruous ice-cream van would creep its lonely way from one hideously uninviting tower block to another, its broken chimes turned up to maximum volume, creating a hellish racket that was somewhere between a nursery rhyme and a death rattle. As far as anyone could tell, it was selling drugs. We called it "The Ice Cream Van of the Apocalypse".

Mugging was a fairly common occurrence in Hulme, as was burglary and the occasional assault by packs of wild dogs. When I first moved into Otterburn Close, my third-floor flat had a pathetically inadequate H-frame door that was one part rotten wood to 10 parts flimsy "security glass". The first time I got burgled, the door was broken so badly that the council were unable to fix it, so they replaced it with a newfangled "security door". Unlike their predecessors these were largely made of wood, with three tiny window slats allowing the people inside to look out without allowing everyone outside to come in. These new doors were such a whizzo idea that everyone wanted one and the council just couldn't keep up with demand.

The next time I got burgled, they stole the door.

Such was life in Hulme.

One day, a man from the council popped in to visit a friend of mine called Phil, who had accidentally agreed to take part in a survey of some sort. All he had to do was answer a few very simple questions about the state of his flat and his experience of living in Hulme.

"How is the flat?" asked the man with the clipboard. "All fine?"

"Oh yes," replied Phil, "all absolutely fine. Very good in fact."

"So, no complaints?"

"No, no complaints."

"None whatsoever?"

"No, really, everything's fine."

"I see," said the man from the council, apparently unconvinced. "So all the services in the flat are in full working order?"

"Well," replied Phil, "the boiler doesn't work."

"Ah, I see. And how long has it been out of order?"

"Well," said Phil, "that's hard to say because it wasn't working when we got here."

"And how long ago was that?"

"About three years ago."

"Three years?"

"Yes. About that."

"So your boiler hasn't worked for at least three years?"

"No. But, you know, we make do…"

"I see. And is there anything else that doesn't work?"

"Well, of course the intercom's never been connected, so technically that "doesn't work", although it's not as if it's broken – it's just not there. And the downstairs toilet's bust. But it's only the downstairs one, so, hey. And the kitchen sink leaks, so we use a bowl. Which is fine. And come to think of it the asbestos has started to crumble and leave little white flakes all over the inside of the boiler cupboard which is probably rather dangerous. But it's not a problem because, to be honest, we rarely open the boiler-cupboard door anyway."

"Because the boiler doesn't work?"

"No, because of the cockroaches."

"I see," said the man from the council, laying his clipboard on his lap. "I'm afraid we've come across this rather a lot.

It's called 'diminished expectations'."

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that the people who think they enjoyed POTC3 are simply suffering from the cinematic equivalent of long-term deprivation of the basics of a civilised existence. They are the multiplex dwellers who have become used to living in the cultural freezing cold, whose brains have been addled by poisonous celluloid asbestos, and whose expectations of mainstream entertainment have been gradually eroded by leaky plumbing and infestations of verminous pests.

They are the Audiences of the Apocalypse.

If you don't believe me, ask yourself this question: "Was Pearl Harbor a hit?" The answer, obviously, ought to be a resounding "No". For, as even the lowliest of amoebic life forms can tell you, that film was shockingly poor in ways it is almost painful to imagine. For one thing, it is "un film de Michael Bay", the reigning deity of all that is loathsome, putrid and soul-destroying about modern-day blockbuster entertainment.

"There are tons of people who hate me," admits Bay, who turned an innocuous TV-and-toys franchise into puerile pop pornography with his headache-inducing Transformers movies. "They said that I wrecked cinema. But hey, my movies have made a lot of money around the world." If you want kids' movies in which cameras crawl up young women's skirts while CGI robots hit each other over the head, interspersed with jokes about masturbation and borderline-racist sub-minstrelsy stereotyping, then Bay is your go-to guy. He is also, shockingly, one of the most commercially successful directors working in Hollywood today, a hit-maker who proudly describes his visual style as "fucking the frame" and whose movies appear to have been put together by people who have just snorted two tonnes of weapons-grade plutonium. Don't get me wrong – he's not stupid; he publicly admitted that Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen was below even his own poor par (his exact words were "When I look back at it, that was crap"), after leading man and charisma vacuum Shia LaBeouf declared that he "wasn't impressed with what we did". But somehow Bay's awareness of his own films' awfulness simply makes matters worse. At least Ed Wood, director of Plan 9 from Outer Space, thought the trash he was making was good. Bay seems to know better and, if he does, that knowledge merely compounds his guilt. Down in the deepest bowels of the abyss there is a 10th circle of hell in which Bay's movies play for all eternity, waiting for their creator to arrive, his soul tortured by the realisation that he knew what he was doing…

But I digress. Back to Pearl Harbor. In early 2001, Pearl Harbor was the most eagerly awaited blockbuster of the summer season. The script was by Randall Wallace, whose previous piece of historical balderdash was the Oscar-winning Braveheart, a movie that allegedly advanced the cause of Scottish nationalism with its shots of lochs, thistles, and men in kilts and blue woad eating haggis to the sound of bagpipes (although most of it was actually shot in Ireland after someone cut a canny deal with the government to use the An Fórsa Cosanta Áitiúil as extras – Viva William Wallace!). As a writer who appears to have a flimsy grasp of history, and who would have us believe that it is possible for men to deliver defiant speeches whilst having their intestines removed on a rack, Wallace was the perfect choice to pen a movie about the worst military disaster in US history in which "America wins!" The fact that Pearl Harbor (the movie) would attempt this revisionist coup de grâce in the same year that America suffered its worst attack on home soil since Pearl Harbor (the real disaster, rather than the movie) could not have been predicted by the film-makers.

But the fact that they were making one of the worst pieces of crap to grace movie theatres in living memory should have been horribly apparent to anyone who had read that bloody awful screenplay. Bad writing is one thing – bad reading is unforgivable. Wallace may be a rotten screenwriter (he writes lines that even Ben Affleck looks embarrassed to deliver), but it was Michael Bay and Pirates of the Caribbean producer Jerry Bruckheimer who gave him the go-ahead, and who must therefore shoulder the blame.

Anyway, the film got made and released, with the full support of the US navy who gave the film-makers access to their military hardware and staged a premiere party by a graveyard (the eponymous harbour) to the shock and awe of relatives of the dead. Hey ho. The reviews were terrible, though I was personally guilty of the most atrociously contrary humbug by attempting to claim that the movie really wasn't as utterly awful as everyone was saying. What the hell was I thinking? Looking back on it now, I shudder to remember just how lenient I had been – how I had claimed that the film offered a brainless spectacle in the now time-honoured tradition of summer blockbusters, about which I had recently written a stupidly enthusiastic article for some glossy publication from whom I was frankly flattered to receive a commission. It was a shameful misjudgment, which I will carry with me to my grave, and I fully expect to be joining Mr Bay in that multiplex in hell, racked by the guilty knowledge that I just stood by and allowed this horror to happen.

Never trust a critic.

Especially this critic.

Others, however, were more forthright and correctly identified Pearl Harbor for the cack that it so clearly was. Audiences were in agreement – the vast majority of the emailed comments that Simon Mayo and I received at our BBC 5 Live radio show from people who had shelled out good money to watch Pearl Harbor were roundly condemnatory, and many were genuinely flabbergasted by just how boring the movie had been.

So, the film was a flop, right?

Wrong.

Wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong.

Listen…

During production, there was much trade-press tooth-sucking about the fact that Pearl Harbor's "authorised starting budget" was $135m, a record-breaking sum back then. Bay and Bruckheimer had originally wanted $208m, and the director was widely reported to have "walked" on several occasions as arguments about how much money the movie should cost continued. As the story of the budget grew, Bay and Bruckheimer very publicly agreed to take $4m salary cuts (in return for a percentage of the profits – clever) to "keep the budget down", thereby giving the impression that every cent spent would be up there on screen. The final cost of the film was somewhere between $140m and $160m, figures gleefully quoted by negative reviewers who spied a massive flop ahoy and predicted chastening financial losses. Yet in Variety's annual roundup of the biggest grossing movies of 2001, Pearl Harbor came in at number six, having taken just shy of $200m in the US alone. By the time the film had finished its worldwide theatrical run, this abomination had raked in a staggering $450m, helping to push Buena Vista International's takings over the $1bn mark for the seventh consecutive year. No matter that almost everyone who saw the film found it a crushing disappointment – as far as the dollars were concerned, Pearl Harbor was an unconditional hit.

It gets worse. Having more than made its money back in cinemas, Pearl Harbor went on to become an equally outrageous success on DVD, the release of the money-spinning disc tastefully timed to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the original attack. Available in "several packages, including a gift set" (and at 183 minutes, Pearl Harbor is the gift that just keeps on giving), the DVD included a commentary track by Michael Bay who was apparently aware that his bold attempts to make a 1940s-style romance had been misinterpreted by some viewers as simply rubbish. Presumably it wasn't the film that was at fault – it was the film's critics who just weren't up to it.

So why did so many people pay for it?

One answer is "diminished expectations": the film was a summer blockbuster, which everyone (myself included) expected to be utterly terrible before they saw it, and so no one was surprised when it turned out to be every bit as dire as predicted. But why pay to see something that you know in advance is going to be a disappointment? The truth is that, like it or loathe it, Pearl Harbor was "an event" – a film that made headlines long before the cameras turned thanks to its bloated budget, and which managed to stay in the headlines throughout its production courtesy of a unique mix of historical tactlessness, fatuous movie-star flashing (Kate Beckinsale reportedly displayed her naked bottom during a no-pants flypast – whoopee!) and, most importantly, enormous expense. Remember that story about Bay and Bruckheimer cutting their salaries? For whose benefit do you think that story was planted? And what about the account (dutifully repeated on the film's Internet Movie Database entry) that "the after-premiere party for Pearl Harbor is said to have cost more than the production costs for Billy Elliot". Or that "Michael Bay quit the project four times over various budgetary disputes". Or, best of all, that "the total amount of money spent on production and promotion roughly equalled the amount of damage caused in the actual attack".

Even though some of these stories may appear at first glance to be mocking the movie and its grotesque expense, they are all in fact a publicist's wet dream, and you can be pretty much guaranteed that the only reason we know about any of them is because some publicist somewhere told someone who would in turn tell us. This is how movie publicity works – with very rare exceptions, everything you know about a movie (at least during its initial release period) is a sales pitch. Even the reviews, about which film-makers regularly bleat and whinge and moan, are part of this sales process, raising the profile of the product. Why else would the studios go to the bother and expense of putting on private pre-release screenings for critics who may very well savage their product? If they really thought the reviews were going to hurt the movie, or have zero beneficial effect upon its box office, they wouldn't press screen them at all.

I have yet to see any evidence that bad reviews can in fact damage a film's box office. With Pearl Harbor (which was proudly screened to critics around the world) you can be sure that the piss-poor reviews it provoked were all part of the plan. Oh, I'm not claiming that the distributors wanted the critics to hate the movie – they would have preferred glowing notices praising its universal love story and drooling over its expensive special effects. But they will have known in advance that the reviews were going to be generally negative (because the film itself was so bad) and they went ahead with those press screenings anyway. Crucially, there were no "long lead" previews, which are used to generate positive word-of-mouth buzz and to build audience awareness of titles that people might actually like. Instead, the film was screened as close to its release date as possible, ensuring that by the time the reviews (good or bad) appeared, the film was available for viewing by paying punters eager to see what all the fuss was about. And, as planned, many (if not most) of those reviews referred at some point to the whopping budget, about which the publicists had been priming us all since pre-production. However scathing a particular review may have been, the reader (or listener, or viewer) would come away having been reminded that Pearl Harbor cost a vast amount of money, and understanding that, for the price of a ticket, he or she could see where all that money had gone. Rather than the stars, the money was the story. And in today's marketplace, that's a story which almost always has a happy ending.

Every time I complain that a blockbuster movie is directorially dumb, or insultingly scripted, or crappily acted, or artistically barren, I get a torrent of emails from alleged mainstream-movie lovers complaining that I (as a snotty critic) am applying highbrow criteria that cannot and should not be applied to good old undemanding blockbuster entertainment. I am not alone in this; every critic worth their salt has been lectured about their distance from the demands of "popular cinema", or has been told that their views are somehow elitist and out of touch (and if you haven't been told this then you are not a critic, you are a "showbiz correspondent"). This has become the shrieking refrain of 21st-century film (anti)culture – the idea that critics are just too clever for their own good, have seen too many movies to know what the average punter wants, and are therefore sorely unqualified to pass judgment on the popcorn fodder that "real" cinema-goers demand from the movies.

This is baloney – and worse, it is pernicious baloney peddled by people who are only interested in money and don't give a damn about cinema. The problem with movies today is not that "real" cinema-goers love garbage while critics only like poncy foreign language arthouse fare. The problem is that we've all learned to tolerate a level of overpaid, institutionalised corporate dreadfulness that no one actually likes but everyone meekly accepts because we've all been told that blockbuster movies have to be stupid to survive. Being intelligent will cause them to become unpopular. Duh! The more money you spend, the dumb and dumberer you have to be. You know the drill: no one went broke underestimating the public intelligence. That's just how it is, OK?

Well, actually, no. You want proof? OK. Exhibit A: Inception.

Inception is an artistically ambitious and intellectually challenging thriller from writer/director Christopher Nolan, who made his name with the temporally dislocated low- budget "arthouse" puzzler Memento. Nolan unfashionably imagines that his audience are sentient beings, and treats them as such regardless of budget. Memento cost $5m, had no stars or special effects, aimed high nonetheless, expected its audience to keep up, and reaped over $25m in the US alone. Inception cost $160m, had huge stars and blinding special effects, aimed high nonetheless, expected its audience to keep up, and took around $800m worldwide. See a connection here?

Nolan earned the right to make a movie as intelligent and expensive as Inception by grossing Warner Bros close to $1.5bn with Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, both of which can best be described as arthouse movies posing as massive franchise blockbusters. I remember being genuinely stunned by the level of invention at work in Batman Begins, and burbling to Radio 5 Live listeners that it was "far, far smarter than any of us had the right to expect from a movie which cost that much". But why shouldn't it be smart? Why shouldn't we expect movies that "cost that much" to be worth it?

Because we have been told for too long that popular movies must, by their very nature, be terrible, and we've all learned to accept this horrendous untruth.

As for Inception, the idea that a "mainstream" audience could embrace a movie that includes the lines "Sorry, whose dream are we in?" and "He's militarised his subconscious!" would seem anathema to the studio heads (and their mealy- mouthed media minions), who have been telling us for decades that dumb is beautiful. Yet Nolan has become one of the most financially reliable directors working in Hollywood without ever checking his intellect in at the door. Did no one explain the rules to him? Did he miss a meeting?

Don't get me wrong; Inception isn't perfect, nor is it "stunningly original", as some would have you believe. The plot, which revolves around explosive industrial espionage played out within the interlocking layers of an unsuspecting psyche, is essentially Dreamscape with A-levels and draws upon a number of populist sources, ranging from Wes Craven's horror sequel A Nightmare on Elm Street: Dream Warriors to Alejandro Amenábar's Spanish oddity Open Your Eyes (later remade in Hollywood as the inferior Tom Cruise vehicle Vanilla Sky). It is also, in essence, an existential Bond movie: On Her Majesty's Psychiatric Service. But like great pop music, groundbreaking cinema rarely arrives ex nihilo, and the fact that Nolan seems to have watched (and loved) a lot of genre trash in his time merely increases his significant stature in my eyes.

Too many blockbuster movies nowadays seem to be made by people who hate cinema, who have seen too few movies, and who have nothing but contempt for the audiences who pay their grotesquely over-inflated salaries. So, did Inception become a money-spinning hit because it boasts a really smart script?

I'd like to think so, but honestly, no.

Would it have taken less money if it had been less intelligent?

Maybe. Probably not. Who knows?

Would it have taken more money if it been less intelligent?

Maybe. Probably not. Who knows?

Would it have made anything like that amount of money if it didn't include:

a) an A-list star

b) eye-popping special effects

c) a newsworthy budget?

Definitely not.

So what does the success – both financial and artistic – of Inception prove? Simply this: that if you spend enough money, bag an A-list star and pile on the spectacle, the chances are your movie will not lose money, regardless of how smart or dumb it may be. Trying to be funny may be a massive risk (fail and your movie goes down) but trying to be clever never hurt anyone. Clearly, the exact amount of money a movie will ultimately make will be affected to some degree by whether or not anyone actually likes it; Titanic couldn't have become a record-breaking profit-maker if some people hadn't wanted to see it twice, and whatever my own personal problems with the film I concede that loads of people really do love it to pieces. But the fact remains that, if you obey the three rules of blockbuster entertainment, an intelligent script will not (as is widely claimed) make your movie tank or alienate your core audience. Even if they don't understand the film, they'll show up and pay to see it anyway – in just the same way they'll flock to see films that are rubbish, and which they don't actually enjoy. Like Pearl Harbor.

This may sound like a terribly depressing scenario – that multiplex audiences will stump up for "event movies" regardless of their quality. But look at it this way: if the audiences will show up whether a movie is good or bad, then does the opportunity not exist to make something genuinely adventurous with little or no risk? If the studio's money is safe regardless of what they do, artistically speaking, why not do something of which they can be proud? If you're working in a marketplace in which the right kind of gargantuan expense all but guarantees equivalent returns, where's the downside in pushing the artistic envelope? Why dumb down when the dollar is going up?

Why be Michael Bay when you could be Christopher Nolan? In fact, despite the asinine whining of those cultural collaborators who have invested their fortunes in the presumption of the stupidity of others, the blockbuster market arguably offers a level of artistic freedom that no other sector of film financing enjoys. The idea that creative risk must be limited to low or mid-priced movie-making (where you can in fact lose loads of money) while thick-headed reductionism rules the big-budget roost is in fact the very opposite of the truth.

As David Puttnam has been saying for years, the biggest risk in Hollywood at the moment is making a mid-priced, artistically adventurous movie which has a great script but no stars or special effects, ie the kind of film that studios now view as potential financial Kryptonite. It is this area in which producers can most legitimately be forgiven for following a policy of cultural risk avoidance, because it is here that monetary shirts may still be lost. Remember – The Shawshank Redemption, a prison drama with no marquee-name stars or special effects, actually lost money in cinemas (it cost $35m, of which it recouped only $18m in its initial release period) before it went on to become one of the most popular movies of all time on home video. If it had cost $200m, starred Tom Cruise and featured a couple of explosive break-out sequences, it would have broken even in the first few weeks – guaranteed.

For further proof of money's ability to make more money, look at the list of the most expensive movies of the past 20 years and see how infrequently they have failed to turn a profit, regardless of quality. Sam Raimi's baggily substandard Spider-Man 3, which even the fans agree was a calamitous mess (unlike the first two instalments) cost $258m and grossed $885m worldwide. X-Men: The Last Stand, which tested the patience of devotees of both the comic books and the movies, ran up a bill of $210m but still raked in $455m worldwide. James Cameron's Avatar (aka Smurfahontas, or Dances with Smurfs) cost $237m and (if we include the unnecessarily extended "Special Edition' re-release) has achieved global box-office takings just shy of $2.8bn.

Even David Fincher's utterly up-itself The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, an upmarket indulgence in which Brad Pitt plays a man who lives his life backwards, managed to balance its $150m costs with worldwide box-office takings in the region of $329m, thanks in part to well-placed news stories about its ultra-expensive special effects. If you take the oft-repeated industry maxim that a film must gross twice its negative cost (the price of actually making the film before incurring print, publicity and distribution costs) in order to earn its keep, then all of these movies were bona fide hits. Working on the same ratio, Bryan Singer's dangerously star-free 2006 superhero flick Superman Returns, featuring Brandon "who he?' Routh, "underperformed' at the box office, with takings of $390m just failing to balance its official cost of $209m (as opposed to the $270m some reported) although ancillary revenues would certainly have pushed it into profit.

Compare that with Spike Jonze's Where the Wild Things Are, which I really liked (although crucially my kids didn't) but which only a fool would have financed to the tune of $100m, since it contained no stars (Catherine Keener is an indie queen, James Gandolfini a safe bet only on TV) and boasted deliberately unspectacular (but nonetheless costly) special effects.

Like Heaven's Gate, Where the Wild Things Are was a movie whose budget was totally out of whack with the financial realities of what was on-screen, and it has been widely described as a chastening flop. Jonze's folly still took around $100m in theatres worldwide and has since recouped more on DVD and TV, meaning that the level of its "failure' is far from studio-sinkingly spectacular. Once upon a time, a film like Where the Wild Things Are would have ended Spike Jonze's career and sent industry bosses tumbling from high windows. Today, it is merely a curio from which everyone will walk away unscathed.

This is the not-so-harsh reality of the movie business for top-end productions in the 21st century. For all the bleating and moaning and carping and whingeing that we constantly hear about studios struggling to make ends meet in the multimedia age, those with the means to splash money around will always come out on top. So the next time you pay good money to watch a really lousy summer blockbuster, remember this: the people who made that movie are wallowing in an endless ocean of cash, which isn't going to dry up any time soon. They are floating on the financial equivalent of the Dead Sea, an expanse of water so full of rotting bodies turned to salt that it is literally impossible for them to sink. They could make better movies if they wanted, and the opulent ripples of buoyant hard currency would still continue to lap at their fattening suntanned bodies. If they fail to entertain, engage and amaze you, then it is because they can't be bothered to do better. And if you accept that, then you are every bit as stupid as they think you are.

This is no time to be nice to big-budget movies. This is the time for them to start paying their way, both financially and artistically.

Extracted from The Good, The Bad and The Multiplex: What's Wrong with Modern Movies? by Mark Kermode. Published by Random House Books on 1 September at GBP 11.99. Copyright Mark Kermode 2011.

1. The world is round.

2. We are all going to die.

3. No one enjoyed Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End.

Oh, I know loads of people paid to see POTC3 (as I believe it is known in the industry). And some of them may claim to have enjoyed it. But they didn't. Not really. They just think they did. As a film critic, an important part of my job is explaining to people why they haven't actually enjoyed a movie even if they think they have. In the case of POTC3, the explanation is very simple.

It's called "diminished expectations".Let me give you an example.

When I was a student in Manchester I lived in a place called Hulme, a sprawling concrete estate of industrially produced deck-access housing that had been declared unfit for families in the mid-70s and had subsequently descended into oddly bohemian squalor. By the time I arrived in Hulme in the early 80s it was full of students who loved it, because the rent was incredibly cheap and nobody paid it anyway – the council couldn't evict you for non-payment because that would just make you homeless and Hulme was the place to which they sent homeless people after they'd been thrown out of everywhere else.

The architecture of Hulme was a strange mix of 60s sci-fi futurism and bleak eastern European uniformity, the kind of place JG Ballard had nightmares about. It was grimly cinematic, so much so that the photographer Kevin Cummins had used it as the background for his iconic photographs of Joy Division, the most existentially miserable band of the 70s. At nights, as the sun went down and the lights came up around the McEwan's beer factory, which wafted noxious fumes across the entire misbegotten district, it seemed more like a scene from Blade Runner than the landscape of a thriving northern town. At regular intervals gangs of straggle-haired youths, who appeared to have escaped from the set of Mad Max 2, would drift across the overpass that traversed the Mancunian Way, shopping trolleys of worthless loot pushed religiously before them and umpteen dogs on various bits of string prowling behind them picking off survivors. Occasionally, an incongruous ice-cream van would creep its lonely way from one hideously uninviting tower block to another, its broken chimes turned up to maximum volume, creating a hellish racket that was somewhere between a nursery rhyme and a death rattle. As far as anyone could tell, it was selling drugs. We called it "The Ice Cream Van of the Apocalypse".

Mugging was a fairly common occurrence in Hulme, as was burglary and the occasional assault by packs of wild dogs. When I first moved into Otterburn Close, my third-floor flat had a pathetically inadequate H-frame door that was one part rotten wood to 10 parts flimsy "security glass". The first time I got burgled, the door was broken so badly that the council were unable to fix it, so they replaced it with a newfangled "security door". Unlike their predecessors these were largely made of wood, with three tiny window slats allowing the people inside to look out without allowing everyone outside to come in. These new doors were such a whizzo idea that everyone wanted one and the council just couldn't keep up with demand.

The next time I got burgled, they stole the door.

Such was life in Hulme.

One day, a man from the council popped in to visit a friend of mine called Phil, who had accidentally agreed to take part in a survey of some sort. All he had to do was answer a few very simple questions about the state of his flat and his experience of living in Hulme.

"How is the flat?" asked the man with the clipboard. "All fine?"

"Oh yes," replied Phil, "all absolutely fine. Very good in fact."

"So, no complaints?"

"No, no complaints."

"None whatsoever?"

"No, really, everything's fine."

"I see," said the man from the council, apparently unconvinced. "So all the services in the flat are in full working order?"

"Well," replied Phil, "the boiler doesn't work."

"Ah, I see. And how long has it been out of order?"

"Well," said Phil, "that's hard to say because it wasn't working when we got here."

"And how long ago was that?"

"About three years ago."

"Three years?"

"Yes. About that."

"So your boiler hasn't worked for at least three years?"

"No. But, you know, we make do…"

"I see. And is there anything else that doesn't work?"

"Well, of course the intercom's never been connected, so technically that "doesn't work", although it's not as if it's broken – it's just not there. And the downstairs toilet's bust. But it's only the downstairs one, so, hey. And the kitchen sink leaks, so we use a bowl. Which is fine. And come to think of it the asbestos has started to crumble and leave little white flakes all over the inside of the boiler cupboard which is probably rather dangerous. But it's not a problem because, to be honest, we rarely open the boiler-cupboard door anyway."

"Because the boiler doesn't work?"

"No, because of the cockroaches."

"I see," said the man from the council, laying his clipboard on his lap. "I'm afraid we've come across this rather a lot.

It's called 'diminished expectations'."

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that the people who think they enjoyed POTC3 are simply suffering from the cinematic equivalent of long-term deprivation of the basics of a civilised existence. They are the multiplex dwellers who have become used to living in the cultural freezing cold, whose brains have been addled by poisonous celluloid asbestos, and whose expectations of mainstream entertainment have been gradually eroded by leaky plumbing and infestations of verminous pests.

They are the Audiences of the Apocalypse.

How did they get here? The short answer is: Michael Bay. The long answer is: Michael Bay; Kevin Costner's gills; Cleopatra on home video; and the inability of modern blockbusters to lose money in the long run, provided they boast star names, lavish spectacle and "event" status expense. Oh, and they don't try to be funny…

"There are tons of people who hate me," admits Bay, who turned an innocuous TV-and-toys franchise into puerile pop pornography with his headache-inducing Transformers movies. "They said that I wrecked cinema. But hey, my movies have made a lot of money around the world." If you want kids' movies in which cameras crawl up young women's skirts while CGI robots hit each other over the head, interspersed with jokes about masturbation and borderline-racist sub-minstrelsy stereotyping, then Bay is your go-to guy. He is also, shockingly, one of the most commercially successful directors working in Hollywood today, a hit-maker who proudly describes his visual style as "fucking the frame" and whose movies appear to have been put together by people who have just snorted two tonnes of weapons-grade plutonium. Don't get me wrong – he's not stupid; he publicly admitted that Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen was below even his own poor par (his exact words were "When I look back at it, that was crap"), after leading man and charisma vacuum Shia LaBeouf declared that he "wasn't impressed with what we did". But somehow Bay's awareness of his own films' awfulness simply makes matters worse. At least Ed Wood, director of Plan 9 from Outer Space, thought the trash he was making was good. Bay seems to know better and, if he does, that knowledge merely compounds his guilt. Down in the deepest bowels of the abyss there is a 10th circle of hell in which Bay's movies play for all eternity, waiting for their creator to arrive, his soul tortured by the realisation that he knew what he was doing…

But I digress. Back to Pearl Harbor. In early 2001, Pearl Harbor was the most eagerly awaited blockbuster of the summer season. The script was by Randall Wallace, whose previous piece of historical balderdash was the Oscar-winning Braveheart, a movie that allegedly advanced the cause of Scottish nationalism with its shots of lochs, thistles, and men in kilts and blue woad eating haggis to the sound of bagpipes (although most of it was actually shot in Ireland after someone cut a canny deal with the government to use the An Fórsa Cosanta Áitiúil as extras – Viva William Wallace!). As a writer who appears to have a flimsy grasp of history, and who would have us believe that it is possible for men to deliver defiant speeches whilst having their intestines removed on a rack, Wallace was the perfect choice to pen a movie about the worst military disaster in US history in which "America wins!" The fact that Pearl Harbor (the movie) would attempt this revisionist coup de grâce in the same year that America suffered its worst attack on home soil since Pearl Harbor (the real disaster, rather than the movie) could not have been predicted by the film-makers.

But the fact that they were making one of the worst pieces of crap to grace movie theatres in living memory should have been horribly apparent to anyone who had read that bloody awful screenplay. Bad writing is one thing – bad reading is unforgivable. Wallace may be a rotten screenwriter (he writes lines that even Ben Affleck looks embarrassed to deliver), but it was Michael Bay and Pirates of the Caribbean producer Jerry Bruckheimer who gave him the go-ahead, and who must therefore shoulder the blame.

Anyway, the film got made and released, with the full support of the US navy who gave the film-makers access to their military hardware and staged a premiere party by a graveyard (the eponymous harbour) to the shock and awe of relatives of the dead. Hey ho. The reviews were terrible, though I was personally guilty of the most atrociously contrary humbug by attempting to claim that the movie really wasn't as utterly awful as everyone was saying. What the hell was I thinking? Looking back on it now, I shudder to remember just how lenient I had been – how I had claimed that the film offered a brainless spectacle in the now time-honoured tradition of summer blockbusters, about which I had recently written a stupidly enthusiastic article for some glossy publication from whom I was frankly flattered to receive a commission. It was a shameful misjudgment, which I will carry with me to my grave, and I fully expect to be joining Mr Bay in that multiplex in hell, racked by the guilty knowledge that I just stood by and allowed this horror to happen.

Never trust a critic.

Especially this critic.

Others, however, were more forthright and correctly identified Pearl Harbor for the cack that it so clearly was. Audiences were in agreement – the vast majority of the emailed comments that Simon Mayo and I received at our BBC 5 Live radio show from people who had shelled out good money to watch Pearl Harbor were roundly condemnatory, and many were genuinely flabbergasted by just how boring the movie had been.

So, the film was a flop, right?

Wrong.

Wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong.

Listen…

During production, there was much trade-press tooth-sucking about the fact that Pearl Harbor's "authorised starting budget" was $135m, a record-breaking sum back then. Bay and Bruckheimer had originally wanted $208m, and the director was widely reported to have "walked" on several occasions as arguments about how much money the movie should cost continued. As the story of the budget grew, Bay and Bruckheimer very publicly agreed to take $4m salary cuts (in return for a percentage of the profits – clever) to "keep the budget down", thereby giving the impression that every cent spent would be up there on screen. The final cost of the film was somewhere between $140m and $160m, figures gleefully quoted by negative reviewers who spied a massive flop ahoy and predicted chastening financial losses. Yet in Variety's annual roundup of the biggest grossing movies of 2001, Pearl Harbor came in at number six, having taken just shy of $200m in the US alone. By the time the film had finished its worldwide theatrical run, this abomination had raked in a staggering $450m, helping to push Buena Vista International's takings over the $1bn mark for the seventh consecutive year. No matter that almost everyone who saw the film found it a crushing disappointment – as far as the dollars were concerned, Pearl Harbor was an unconditional hit.

It gets worse. Having more than made its money back in cinemas, Pearl Harbor went on to become an equally outrageous success on DVD, the release of the money-spinning disc tastefully timed to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the original attack. Available in "several packages, including a gift set" (and at 183 minutes, Pearl Harbor is the gift that just keeps on giving), the DVD included a commentary track by Michael Bay who was apparently aware that his bold attempts to make a 1940s-style romance had been misinterpreted by some viewers as simply rubbish. Presumably it wasn't the film that was at fault – it was the film's critics who just weren't up to it.

So why did so many people pay for it?

One answer is "diminished expectations": the film was a summer blockbuster, which everyone (myself included) expected to be utterly terrible before they saw it, and so no one was surprised when it turned out to be every bit as dire as predicted. But why pay to see something that you know in advance is going to be a disappointment? The truth is that, like it or loathe it, Pearl Harbor was "an event" – a film that made headlines long before the cameras turned thanks to its bloated budget, and which managed to stay in the headlines throughout its production courtesy of a unique mix of historical tactlessness, fatuous movie-star flashing (Kate Beckinsale reportedly displayed her naked bottom during a no-pants flypast – whoopee!) and, most importantly, enormous expense. Remember that story about Bay and Bruckheimer cutting their salaries? For whose benefit do you think that story was planted? And what about the account (dutifully repeated on the film's Internet Movie Database entry) that "the after-premiere party for Pearl Harbor is said to have cost more than the production costs for Billy Elliot". Or that "Michael Bay quit the project four times over various budgetary disputes". Or, best of all, that "the total amount of money spent on production and promotion roughly equalled the amount of damage caused in the actual attack".

Even though some of these stories may appear at first glance to be mocking the movie and its grotesque expense, they are all in fact a publicist's wet dream, and you can be pretty much guaranteed that the only reason we know about any of them is because some publicist somewhere told someone who would in turn tell us. This is how movie publicity works – with very rare exceptions, everything you know about a movie (at least during its initial release period) is a sales pitch. Even the reviews, about which film-makers regularly bleat and whinge and moan, are part of this sales process, raising the profile of the product. Why else would the studios go to the bother and expense of putting on private pre-release screenings for critics who may very well savage their product? If they really thought the reviews were going to hurt the movie, or have zero beneficial effect upon its box office, they wouldn't press screen them at all.

I have yet to see any evidence that bad reviews can in fact damage a film's box office. With Pearl Harbor (which was proudly screened to critics around the world) you can be sure that the piss-poor reviews it provoked were all part of the plan. Oh, I'm not claiming that the distributors wanted the critics to hate the movie – they would have preferred glowing notices praising its universal love story and drooling over its expensive special effects. But they will have known in advance that the reviews were going to be generally negative (because the film itself was so bad) and they went ahead with those press screenings anyway. Crucially, there were no "long lead" previews, which are used to generate positive word-of-mouth buzz and to build audience awareness of titles that people might actually like. Instead, the film was screened as close to its release date as possible, ensuring that by the time the reviews (good or bad) appeared, the film was available for viewing by paying punters eager to see what all the fuss was about. And, as planned, many (if not most) of those reviews referred at some point to the whopping budget, about which the publicists had been priming us all since pre-production. However scathing a particular review may have been, the reader (or listener, or viewer) would come away having been reminded that Pearl Harbor cost a vast amount of money, and understanding that, for the price of a ticket, he or she could see where all that money had gone. Rather than the stars, the money was the story. And in today's marketplace, that's a story which almost always has a happy ending.

Every time I complain that a blockbuster movie is directorially dumb, or insultingly scripted, or crappily acted, or artistically barren, I get a torrent of emails from alleged mainstream-movie lovers complaining that I (as a snotty critic) am applying highbrow criteria that cannot and should not be applied to good old undemanding blockbuster entertainment. I am not alone in this; every critic worth their salt has been lectured about their distance from the demands of "popular cinema", or has been told that their views are somehow elitist and out of touch (and if you haven't been told this then you are not a critic, you are a "showbiz correspondent"). This has become the shrieking refrain of 21st-century film (anti)culture – the idea that critics are just too clever for their own good, have seen too many movies to know what the average punter wants, and are therefore sorely unqualified to pass judgment on the popcorn fodder that "real" cinema-goers demand from the movies.

This is baloney – and worse, it is pernicious baloney peddled by people who are only interested in money and don't give a damn about cinema. The problem with movies today is not that "real" cinema-goers love garbage while critics only like poncy foreign language arthouse fare. The problem is that we've all learned to tolerate a level of overpaid, institutionalised corporate dreadfulness that no one actually likes but everyone meekly accepts because we've all been told that blockbuster movies have to be stupid to survive. Being intelligent will cause them to become unpopular. Duh! The more money you spend, the dumb and dumberer you have to be. You know the drill: no one went broke underestimating the public intelligence. That's just how it is, OK?

Well, actually, no. You want proof? OK. Exhibit A: Inception.

Inception is an artistically ambitious and intellectually challenging thriller from writer/director Christopher Nolan, who made his name with the temporally dislocated low- budget "arthouse" puzzler Memento. Nolan unfashionably imagines that his audience are sentient beings, and treats them as such regardless of budget. Memento cost $5m, had no stars or special effects, aimed high nonetheless, expected its audience to keep up, and reaped over $25m in the US alone. Inception cost $160m, had huge stars and blinding special effects, aimed high nonetheless, expected its audience to keep up, and took around $800m worldwide. See a connection here?

Nolan earned the right to make a movie as intelligent and expensive as Inception by grossing Warner Bros close to $1.5bn with Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, both of which can best be described as arthouse movies posing as massive franchise blockbusters. I remember being genuinely stunned by the level of invention at work in Batman Begins, and burbling to Radio 5 Live listeners that it was "far, far smarter than any of us had the right to expect from a movie which cost that much". But why shouldn't it be smart? Why shouldn't we expect movies that "cost that much" to be worth it?

Because we have been told for too long that popular movies must, by their very nature, be terrible, and we've all learned to accept this horrendous untruth.

As for Inception, the idea that a "mainstream" audience could embrace a movie that includes the lines "Sorry, whose dream are we in?" and "He's militarised his subconscious!" would seem anathema to the studio heads (and their mealy- mouthed media minions), who have been telling us for decades that dumb is beautiful. Yet Nolan has become one of the most financially reliable directors working in Hollywood without ever checking his intellect in at the door. Did no one explain the rules to him? Did he miss a meeting?

Don't get me wrong; Inception isn't perfect, nor is it "stunningly original", as some would have you believe. The plot, which revolves around explosive industrial espionage played out within the interlocking layers of an unsuspecting psyche, is essentially Dreamscape with A-levels and draws upon a number of populist sources, ranging from Wes Craven's horror sequel A Nightmare on Elm Street: Dream Warriors to Alejandro Amenábar's Spanish oddity Open Your Eyes (later remade in Hollywood as the inferior Tom Cruise vehicle Vanilla Sky). It is also, in essence, an existential Bond movie: On Her Majesty's Psychiatric Service. But like great pop music, groundbreaking cinema rarely arrives ex nihilo, and the fact that Nolan seems to have watched (and loved) a lot of genre trash in his time merely increases his significant stature in my eyes.

Too many blockbuster movies nowadays seem to be made by people who hate cinema, who have seen too few movies, and who have nothing but contempt for the audiences who pay their grotesquely over-inflated salaries. So, did Inception become a money-spinning hit because it boasts a really smart script?

I'd like to think so, but honestly, no.

Would it have taken less money if it had been less intelligent?

Maybe. Probably not. Who knows?

Would it have taken more money if it been less intelligent?

Maybe. Probably not. Who knows?

Would it have made anything like that amount of money if it didn't include:

a) an A-list star

b) eye-popping special effects

c) a newsworthy budget?

Definitely not.

So what does the success – both financial and artistic – of Inception prove? Simply this: that if you spend enough money, bag an A-list star and pile on the spectacle, the chances are your movie will not lose money, regardless of how smart or dumb it may be. Trying to be funny may be a massive risk (fail and your movie goes down) but trying to be clever never hurt anyone. Clearly, the exact amount of money a movie will ultimately make will be affected to some degree by whether or not anyone actually likes it; Titanic couldn't have become a record-breaking profit-maker if some people hadn't wanted to see it twice, and whatever my own personal problems with the film I concede that loads of people really do love it to pieces. But the fact remains that, if you obey the three rules of blockbuster entertainment, an intelligent script will not (as is widely claimed) make your movie tank or alienate your core audience. Even if they don't understand the film, they'll show up and pay to see it anyway – in just the same way they'll flock to see films that are rubbish, and which they don't actually enjoy. Like Pearl Harbor.

This may sound like a terribly depressing scenario – that multiplex audiences will stump up for "event movies" regardless of their quality. But look at it this way: if the audiences will show up whether a movie is good or bad, then does the opportunity not exist to make something genuinely adventurous with little or no risk? If the studio's money is safe regardless of what they do, artistically speaking, why not do something of which they can be proud? If you're working in a marketplace in which the right kind of gargantuan expense all but guarantees equivalent returns, where's the downside in pushing the artistic envelope? Why dumb down when the dollar is going up?

Why be Michael Bay when you could be Christopher Nolan? In fact, despite the asinine whining of those cultural collaborators who have invested their fortunes in the presumption of the stupidity of others, the blockbuster market arguably offers a level of artistic freedom that no other sector of film financing enjoys. The idea that creative risk must be limited to low or mid-priced movie-making (where you can in fact lose loads of money) while thick-headed reductionism rules the big-budget roost is in fact the very opposite of the truth.

As David Puttnam has been saying for years, the biggest risk in Hollywood at the moment is making a mid-priced, artistically adventurous movie which has a great script but no stars or special effects, ie the kind of film that studios now view as potential financial Kryptonite. It is this area in which producers can most legitimately be forgiven for following a policy of cultural risk avoidance, because it is here that monetary shirts may still be lost. Remember – The Shawshank Redemption, a prison drama with no marquee-name stars or special effects, actually lost money in cinemas (it cost $35m, of which it recouped only $18m in its initial release period) before it went on to become one of the most popular movies of all time on home video. If it had cost $200m, starred Tom Cruise and featured a couple of explosive break-out sequences, it would have broken even in the first few weeks – guaranteed.

For further proof of money's ability to make more money, look at the list of the most expensive movies of the past 20 years and see how infrequently they have failed to turn a profit, regardless of quality. Sam Raimi's baggily substandard Spider-Man 3, which even the fans agree was a calamitous mess (unlike the first two instalments) cost $258m and grossed $885m worldwide. X-Men: The Last Stand, which tested the patience of devotees of both the comic books and the movies, ran up a bill of $210m but still raked in $455m worldwide. James Cameron's Avatar (aka Smurfahontas, or Dances with Smurfs) cost $237m and (if we include the unnecessarily extended "Special Edition' re-release) has achieved global box-office takings just shy of $2.8bn.

Even David Fincher's utterly up-itself The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, an upmarket indulgence in which Brad Pitt plays a man who lives his life backwards, managed to balance its $150m costs with worldwide box-office takings in the region of $329m, thanks in part to well-placed news stories about its ultra-expensive special effects. If you take the oft-repeated industry maxim that a film must gross twice its negative cost (the price of actually making the film before incurring print, publicity and distribution costs) in order to earn its keep, then all of these movies were bona fide hits. Working on the same ratio, Bryan Singer's dangerously star-free 2006 superhero flick Superman Returns, featuring Brandon "who he?' Routh, "underperformed' at the box office, with takings of $390m just failing to balance its official cost of $209m (as opposed to the $270m some reported) although ancillary revenues would certainly have pushed it into profit.

Compare that with Spike Jonze's Where the Wild Things Are, which I really liked (although crucially my kids didn't) but which only a fool would have financed to the tune of $100m, since it contained no stars (Catherine Keener is an indie queen, James Gandolfini a safe bet only on TV) and boasted deliberately unspectacular (but nonetheless costly) special effects.

Like Heaven's Gate, Where the Wild Things Are was a movie whose budget was totally out of whack with the financial realities of what was on-screen, and it has been widely described as a chastening flop. Jonze's folly still took around $100m in theatres worldwide and has since recouped more on DVD and TV, meaning that the level of its "failure' is far from studio-sinkingly spectacular. Once upon a time, a film like Where the Wild Things Are would have ended Spike Jonze's career and sent industry bosses tumbling from high windows. Today, it is merely a curio from which everyone will walk away unscathed.

This is the not-so-harsh reality of the movie business for top-end productions in the 21st century. For all the bleating and moaning and carping and whingeing that we constantly hear about studios struggling to make ends meet in the multimedia age, those with the means to splash money around will always come out on top. So the next time you pay good money to watch a really lousy summer blockbuster, remember this: the people who made that movie are wallowing in an endless ocean of cash, which isn't going to dry up any time soon. They are floating on the financial equivalent of the Dead Sea, an expanse of water so full of rotting bodies turned to salt that it is literally impossible for them to sink. They could make better movies if they wanted, and the opulent ripples of buoyant hard currency would still continue to lap at their fattening suntanned bodies. If they fail to entertain, engage and amaze you, then it is because they can't be bothered to do better. And if you accept that, then you are every bit as stupid as they think you are.

This is no time to be nice to big-budget movies. This is the time for them to start paying their way, both financially and artistically.

Extracted from The Good, The Bad and The Multiplex: What's Wrong with Modern Movies? by Mark Kermode. Published by Random House Books on 1 September at GBP 11.99. Copyright Mark Kermode 2011.

I totally agree with him. i still wouldnt pay 11,99 for his book

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete